“Eureka!” Food, Craft, and Revisionist History: An Interview with Kedrick McKenzie

Still from California Fruit Salad, a 2 minute 25 second digital video performance.

Space On Space: Does collecting play a role in your work?

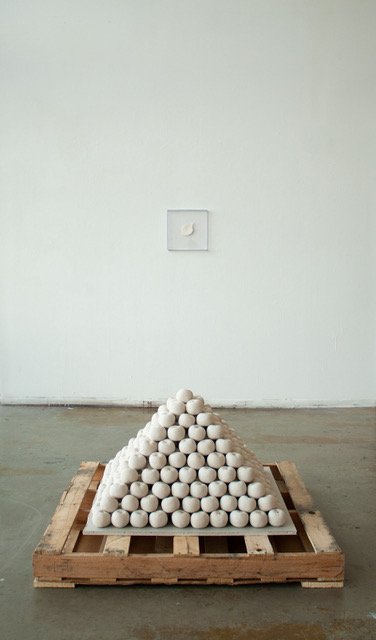

Kedrick McKenzie: My art practice has always included multiples. I love assembling a collection of the same object and playing with meaning through repetition, but I hesitate to call myself a collector. I do love to collect information. I have notebooks filled with seemingly unconnected bits of histories, anecdotes, jokes, and quotes from famous people. Weaving together seemingly disparate information is a core part of my art practice.

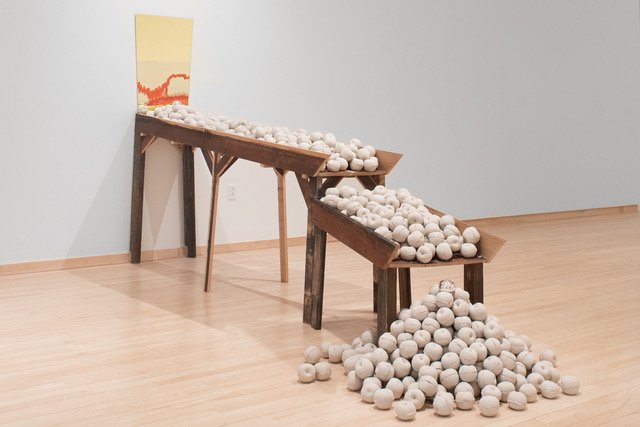

Eureka’s Flow, Progress is a Pitcher Already Filled, unfired clay, salvaged wood, acrylic, mirrored glass. Image courtesy of Neighboring States.

Perpetual Frontier, watercolor on receipt paper, wire shopping basket, vinyl tiles. Image courtesy of Neighboring States.

Portrait of the artist.

SOS: You create objects, sculptures, and performances. Why have you gravitated towards these mediums?

KM: I became an artist because of a ceramics class I took over ten years ago. At the time, I thought that being an artist meant being a painter. I didn’t know that you could be an artist by working in any material. Clay has always been my first love. However, I realized using clay has its limits. My work springs from deep questions about identity and history. Performance became a way for me to heighten the stakes of my work and challenge the audience. I realized I could make a ceramic sculpture that dealt with indulgence and consumption, and I could also record myself shoving Jell-O into my mouth. They are all processes I can play with.

SOS: Why does food, particularly Jell-O, appear a lot in your work?

KM: The work I create is about processing questions of belonging, place, and home. Food sits at an interesting intersection and is often an object of commerce connected to memory, family, and geography. My father is an avid gardener, so my childhood was spent helping him tend to plants in our backyard. The idea of belonging to a place because you grew food from the land interests me. Food can be unifying. Food requires labor. It can be politicized. I find myself particularly interested in the aesthetics of consumption.

Fresh Produce Daily, gelatin, wire shopping basket, heat lamp, motion sensor.

A Natural Pile of Organic Apples, unfired clay, wooden pallet.

Portable Frontier, gelatin, spray paint, wire shopping basket, vinyl tiles. Image courtesy of Neighboring States.

“I find myself particularly interested in the aesthetics of consumption. ”

Jell-O became an interest during grad school. I needed a break from clay and started casting gelatin into molds in my studio. Jell-O is inexpensive and is a stereotypical white person food. It helped open my work up in a way that clay couldn’t. From there, I dove into research about the Jell-O company and gelatin’s long history. One of its more interesting properties is its role as a preserver. Remember those kitschy Jell-O salads that emerged from wartime housewives being told they could be patriotic by preserving their limited rations in gelatin salads? Jell-O became something that encased or suspended other foods. That suspension is interesting to me. I started to imagine Jell-O as a real life version of the 1958 American horror film The Blob. It slowly oozes through American history, congealing around everything in its path.

Wave Pitcher (Orchard City), ceramic, glass, epoxy.

Blossom Pitcher (Orchard City), ceramic, epoxy.

SOS: You just finished up your MFA thesis show called After Eureka, What? Tell us about it.

KM: My thesis exhibition started to emerge when I rediscovered a ceramics manufacturer called Garden City Pottery that used to be in my hometown of San Jose. The craft connection to my hometown struck me. It was one of many small pottery studios working in early 20th-century California. These studios started making single-colored, brightly-glazed pieces that would go on to be emulated through Fiesta dinnerware.

On eBay, I found a bright orange pitcher that was made by Garden City Pottery sometime between 1900-1950. It became my muse in a weird way. Garden City Pottery no longer exists; it stopped making pottery in the 1950s and made pipes and garden pots for a few years before shutting down entirely. The pitcher I now own is this physical object that was made in the same place I was.

While searching for Garden City Pottery pieces, I read about California’s history and the myopia that comes from living on the western edge of this colonized continent. The exclamation of “Eureka!”–which is California’s motto–has permanently connected the state to discovery and prosperity. Ever since the California Gold Rush, it’s been caught up in a churn of new frontiers every few years. From gold, to railroads, to agriculture, to aerospace contracts, to the dot-com bubble, and so on. The expression “Eureka!” originates from the Greek exclamation Archimedes cried after witnessing his body displace water, forging its link to the discovery of something. Yet, any new frontier is predicated on a displacement just as much as it is a discovery. The question “After Eureka, What?” came from a 1982 Wallace Stegner essay where he suggests that the question California has to grapple with in the 20th century is “after prosperity, what?” I modified the question to not just address the prosperity of my home state, but also the displacement that coincides with it.

SOS: Grad school's over. Now what?

KM: I’m working on a new body of work that further investigates the research I’ve done the past two years. I’m researching California Modernist design and mid-century craft objects. I’m also getting to read for pleasure, which is a much needed change. Since my program ended, I've been continuing my studio art practice, applying for shows, finding studio space, budgeting, figuring out how to make money, and seeking more community in Philadelphia.

Portrait of the artist.

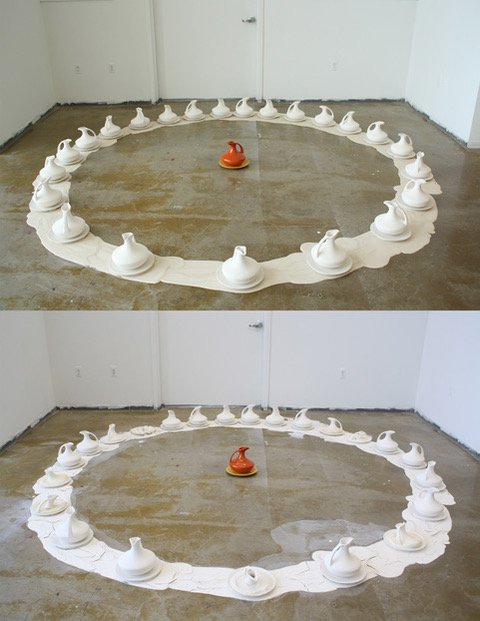

Where We Run Out of Continent (before and after), unfired clay, earthenware.

By combining craft practices with ephemeral materials, Kedrick McKenzie challenges the subjective ways that histories about America are told. Growing up on the West Coast, McKenzie became interested in what lies underneath the folklore of the region. Joan Didion describes California as “a boom mentality and a sense of Chekhovian loss meet[ing] in uneasy suspension.” McKenzie’s practice balances an uneasy combination of the intentional care of craft traditions with extractive practices of consumer culture that occupy American life. Through a combination of research and satire, he examines issues of revisionist history, consumption, and whiteness. By utilizing food as an object and motif that appears frequently in his work, he examines how food is a confluence of economics, culture, and history. Food stories and histories are often shaped by the same colonial, gendered, and racialized logics that have shaped America and by extension, himself.

Kedrick McKenzie working in his studio at Tyler School of Art.