Metabolizing Grief Between Fallow and Fertile

Joliene Adams writes a journal entry-like essay processing the grief of losing her father, undergoing in-vitro fertilization (IVF) treatments, and observing the changing climate along the Oregon Coast Trail.

All images courtesy of Joliene Adams.

Late October 2023 | Oregon Coast Trail, due south.

Where a sunbeam pierced the forest, steam rose in slender columns from spotlit moss. Undulating upwards on northern Oregon Coast Trail switchbacks, I hiked rather than ran. After a recent round of IVF treatments, my ovaries–usually kiwi-sized–were grapefruitish. These hormonally-augmented suckers torsion with strenuous exercise. I savored the dampened hush of a fitful rainy-to-sunny day in temperate rainforest.

IVF involves sixish self-administered daily fertility drug injections to stimulate multiple eggs, increasing the odds a healthy one was produced, retrieved, and fertilized. Sans-IVF, it's one egg per month per person with ovaries.

Thriving Oregon coastal forests resemble a cluttered room. Stuff piled on stuff; you can’t always see the floor but know it’s there. The forest’s understory is a thick mat of ferns, salmonberry, mosses, lichen, rotting logs, fungi, and rhododendrons. I swung my leg over a fallen tree in the path, straddling a trunk so large my feet dangled on either side.

As I stepped back down on the trail, mud ridged up my hiking boot. My belly spilled out over my tights, extra IVF pudge nice n’ squishy like mushroom caps. In Oregon’s coastal forests, a staggering range of fungi sprout with the October arrival of steady autumn rains. They have names like oyster, pine, chicken-of-the-woods, hedgehog, king bolete (porcini), and chanterelle. Chanterelles are Oregon’s state mushroom and the earliest, longest-appearing mushroom in Oregon’s coastal forests. In vitro (Latin)–in glass. Louise Brown, born in 1978, was the first successful live birth via IVF. Eric Danell, in 1995, began the first successful cultivation of a chanterelle in a controlled environment in vitro. Chanterelles depend on complex symbiotic relationships with plant roots, making cultivation outside this environment exceedingly tricky.

Joliene smiling after a round of IVF treatments.

Red belted conk mushrooms (Fomitopsis pinicola) growing from a fallen log.

In vitro fertilization has reproduced far more babies than in vitro origin chanterelles to date. Reproductive resiliency in vitro and in natura. In natura, in ancient times, simply meant birth. In Oregon’s coastal forests, new life sprouted from decay. Observing nurse logs–decomposing fallen trees sprouting seedlings–got me thinking my geriatric ovaries still might have a shot, with IVF, of course…

Post-hike, I packed up for the following day’s road trip. The last thing to go in my car the next morning was a canister of my dad, Charlie’s, ashes, in a cowboy boot.

Joliene’s dad, Charlie’s ashes.

Bennett Pass’ clearing during one of Joliene’s hikes.

Back on the road from the mountain: due east on Highway 26.

Once returned to the car, I upgraded my dad's canister of ashes from the cowboy boot in the backseat to ride shotgun. I secured him with a seatbelt as he’d done many times for young me. Destination: Prineville–Charlie’s hometown and the once bustling logging hub where Fred, his dad, secured a life above the poverty line but deforested the land without fully grasping the consequences.

An hour twenty from Prineville, forested wilderness abruptly opened to an expansive high desert. En route, towns dotted open two-lane highways, narratives of ancient geology striated in roadside rock formations. As a child in the passenger seat on HWY 26, Charlie’s accounts of how all of this used to be underwater riveted me. Ocean waves, over 100 million years ago, covered Oregon and lapped on the shore of today’s Idaho. Across Oregon’s deep history–climates have changed, and landscapes varied. Rhinoceroses roamed here, and tropical forests dominated. Oceans, ice age floodplains, and lava flows forged Oregon’s remarkable geology. Today’s environmental changes are of course distinct–anthropogenic. My nothing of a non-embryo seemed particularly unimportant now.

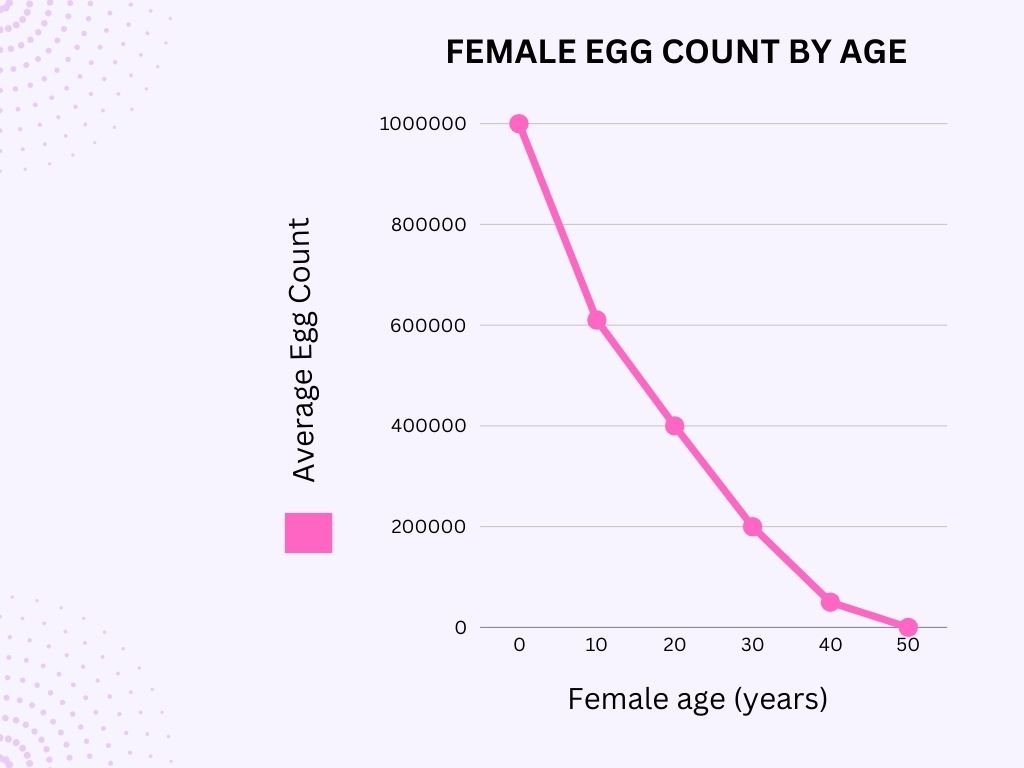

Sagebrush, juniper, jackrabbits, rattlesnakes–life continues in arid expanses despite scarcity. Retrieval one: one viable embryo. Retrieval two: two viable embryos. After genetic testing, the news reversed. Heatwaves of hope became cold fronts of disappointment.

Driving ahead, seated next to Charlie’s ashes, I mourned the parts of him that weren't going to reincarnate in the nine months ahead. Eric and I produced an embryo missing a chromosome. Climates changing, inside my body and out. As for the canister of ashes with the image of Hood on it, a statistically unlikely Central Oregon rainstorm interfered with scattering Charlie’s ashes on Lookout Mountain of the Ochoco Wilderness outside Prineville. So, Charlie rode back home in my cowboy boot. Only this time, the burgundy boot next to him wasn’t empty. It held homemade pickles made by Charlie’s lifelong friend Walt Bolton, who’d graciously offered me a place to stay in Prineville.

March 2024 | Bennett Pass Trail, due east.

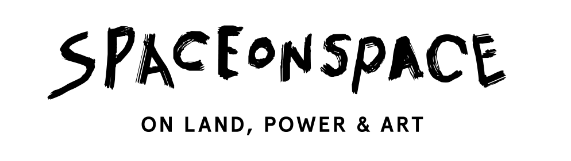

In today’s March blue skies and sunshine, I reached Bennett Pass’ first clearing, dropped my backpack, and sat atop. As my egg count entered irrevocable freefall at age 40, snowmelt occurred in higher volumes and shorter periods in the Pacific Northwest.

Early March on Mt. Hood (Wy’east (1) ) Bennett Pass guarantees snow on the ground and little else. Falling snow, rain, freezing rain, sleet, no precipitation–or worst of all and hardest to dress for–an indecisive end-of-season wintry mix. Daily–sometimes hourly–changes.

A 2023 Oregon Glaciers Institute photographic survey found seven major Hood glaciers receded an average of 60% in the last 120 years, a quarter in the last two decades. “The last time glaciers were stable, and the mountain snowpack, temperatures, and everything was happy and in equilibrium was in the early 1980s,” Daniel O’Neil observed in an 1859 Oregon 2023 issue. Born in 1983 myself, Hood’s snowpack and my eggs were going vamoose in tandem. In May 2023, my 41-year-old partner Eric and I turned to fertility treatments. A visual on why, in large part, we were struggling:

Whatever eggs are left at 40 often aren’t the good shit. Ovaries and eggs age as we do. They become more chromosomally abnormal, leading to more errors in cell division and unviable embryos. You can calculate your odds of a live birth through IVF on the CDC website. My results:

Our third and final retrieval is ahead. As statistical odds increased, my hope remained frozen.

(1) Wy’east is the Indigenous Multnomah tribe’s word for Mt. Hood.

Later that day | Bennett Pass Trail, due east.

Perched on my backpack, I admired the stunning view of Hood’s upper slopes showing zero signs of snowmelt this season. However, down here on this lower-elevation mountain pass, even the trees were sweating, dripping with snowmelt. Accelerated snowmelt in Oregon, a climate crisis consequence, is happening earlier and more intensely. I removed my cobalt beanie, feeling melted snow and sweat trickling down my neck. Lifting one side of my PB&J, crumbled jalapeño chips, I ate. With the aftertaste of salt, sweetness, and SPF, I called upon Charlie.

“Couldn’t you lend a little help with this baby thing, Pops?”

I assumed the deceased had ample free time and maybe some magical powers. I imagined winds carrying my message up the mountain for Charlie to hear. He died unexpectedly on May 11, 2023, days before Eric’s and my planned fertility treatments began. Church spires point towards heaven, like an antenna to God. Charlie and I loved mountains. Mountains are my dadtenna.

I unwound the child-sized hair tie from my nubbin of a bun, reminded of the deforestation of my already fine hair. Nowadays, a combination of stress and genetics, my hair more resembled the spacious forests where Charlie grew up rather than the dense pines and firs where I did. Glacial edges and hairlines: rapid recession, Hood and me. I fully grasp the greater tragedy.

Mountains lack heartbeats but have a lifetime of creation stories. Volcanic activity formed Hood 500,000-700,000 years ago. Tools and fossils unearthed in central Oregon in 2023, indicate humans existed in the PNW a minimum of 18,000 years ago. Based on an imprecise but illustrative 25-year span, that’s 720ish generations past. Humans average 35 million heartbeats a year—630 billion single human heartbeats in adjacency to Hood.

As glaciers melt, ecosystems change, water sources shrink, and cherished landscapes alter. 720 generations of relationships shift. Loss takes different forms: tangible (people, homes), intangible (relationships, identity), and now I understand too, intertangible—things that are both or in between–a ferryman, apparition, fading to gray, glacier still there but on their way out, or failed embryos. Tangible, intangible, intertangible–loss is palpable all the same. And while I’ll always have Rogaine, IVF, and egg donors, Hood’s glaciers may not always have snowpack.

Joliene Adams is an ethically-minded travel and adventure journalist and creative non-fiction writer working on her first book. Her work has been featured in Oregon Humanities, Adventure.com, Fodor’s, and other publications. Besides writing, she leads creative writing residencies and Indigenous language preservation workshops at high schools. Based in the Pacific Northwest, Adams embraces outdoor adventures and emphasizes the importance of connection to place. With dual MA degrees in Comparative Literature and Applied Linguistics, she is also a 2023-2024 Atheneum Master Writing Program Fellow in creative non-fiction at The Attic Literary Center in Portland.